This content block does not have a preview.

I can be myself and work with people in a totally transparent way.

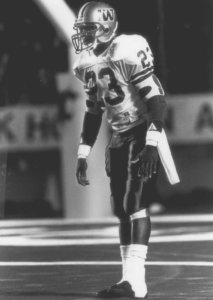

At one point, Walter’s future looked exceptionally bright. A fun-loving UW football star nicknamed “Sweet B,” the Portland native had competed in three Rose Bowls and caught the eye of NFL scouts. But his class-clown persona masked depression that he self-medicated with alcohol.

The football culture encouraged him to drink more and smoke a little pot — like some of his teammates. But as his identity and pride as an athlete grew, so did his substance use disorder.

Looking back, Walter says, “a storm was brewing.”

His tipping point came when the team won the 1991 national college football championship and traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet then-president George H.W. Bush. Walter partied hard and blacked out. He passed out and missed the team visit to the White House.

The next several years were a blur. He hurt his shoulder and didn’t do as well as expected in the NFL Combine, an invite-only event where promising college athletes train in front of NFL scouts. He skipped out on meetings with NFL teams, but eventually signed as a free agent with the New York Giants.

Four months later, the team cut him for failing a drug test. He kicked around the Canadian Football League for a year, but held out hope that he’d make it back to the NFL.

“The lights turned off and the cheering stopped,” Walter says. “I felt like I couldn’t do anything else, so I turned to alcohol and drugs.”

Pills, cocaine, heroin — they filled Walter’s life and pushed him away from his friends, his parents and his two daughters.

“I didn’t know about addiction,” Walter says. “It got worse and I got depressed.”

After a bad car wreck, he ended up back in Portland, living in an abandoned house with others who shared his addiction.

In 2009, Walter checked in to Central City Concern’s Hooper Detoxification Stabilization Center. It was a start, but he began using again as soon as he left. The next year marked his lowest point, as Walter hid out in the drug house while his father got weaker and weaker from prostate cancer.

“The people I loved the most were the people I hurt the most,” he recalls.

That spring, Walter made a decision. He called a childhood friend in recovery and asked for help getting clean. His friend offered the support and stability Walter needed to enter an inpatient treatment program. About six months later, he was relieved to be sober when he said goodbye to his dying father. “I got my baby back,” his dad said, just before he passed away.

For Walter, it was a critical moment of closure: “My father was able to see me as the man I could be.”

After that, he continued to move forward.

“My life began to change and got increasingly better every year,” he says.

He was able to help his mom while staying committed to his sobriety. He began to understand the scientific basis of addiction and how different types of interventions can help people find hope and recover from the disease. Walter spent three years as a counselor, putting his growing knowledge to work.

In 2015, he became a peer mentor at CCC’s Imani Center, a culturally specific recovery program for African American clients. Walter is honest about his past and uses that experience to help clients though their own recoveries.

“I can be myself and work with people in a totally transparent way,” he says.

Now, his life outside work revolves around his family. He cooks, goes on walks and watches movies with his fiancée. Football these days means rooting for the Huskies from his living room couch: “I switched from being an athlete to being a man with values and integrity.”