Este bloque de contenido no tiene vista previa.

There’s a great deal of history at CCC. Since 1979, we’ve had the privilege to breathe new life into some of Portland’s most historic buildings as affordable, supportive housing. These buildings include the Hotel Golden West, the Henry building and The Katherine Gray.

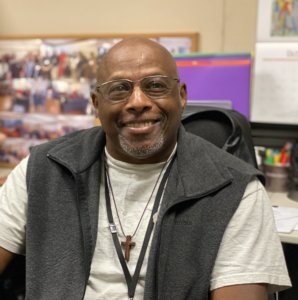

Longtime CCC employee Billy Anfield has entrusted us with sharing some of his family’s story.

But our buildings aren’t the only aspect of CCC imbued with history: our staff with lived experience of homelessness and substance use disorder carry with them their personal histories, too. These stories inform their work as they help our clients achieve stability and success.

One CCC staff member with a great deal of powerful history is Flip the Script Advocacy Coordinator Billy Anfield. Having spent most of the past 30 years working at CCC, Billy has witnessed the agency’s history in the making as we’ve evolved and grown. He also carries rich family and personal histories that we’re honored to share.

Family roots in the South

Billy grew up hearing about his great-uncle Dr. Roman T. Adair, the son of Jane and Green Adair, who were both formerly enslaved. Roman made his parents proud by growing up to be one of the earliest Black physicians in Alabama.

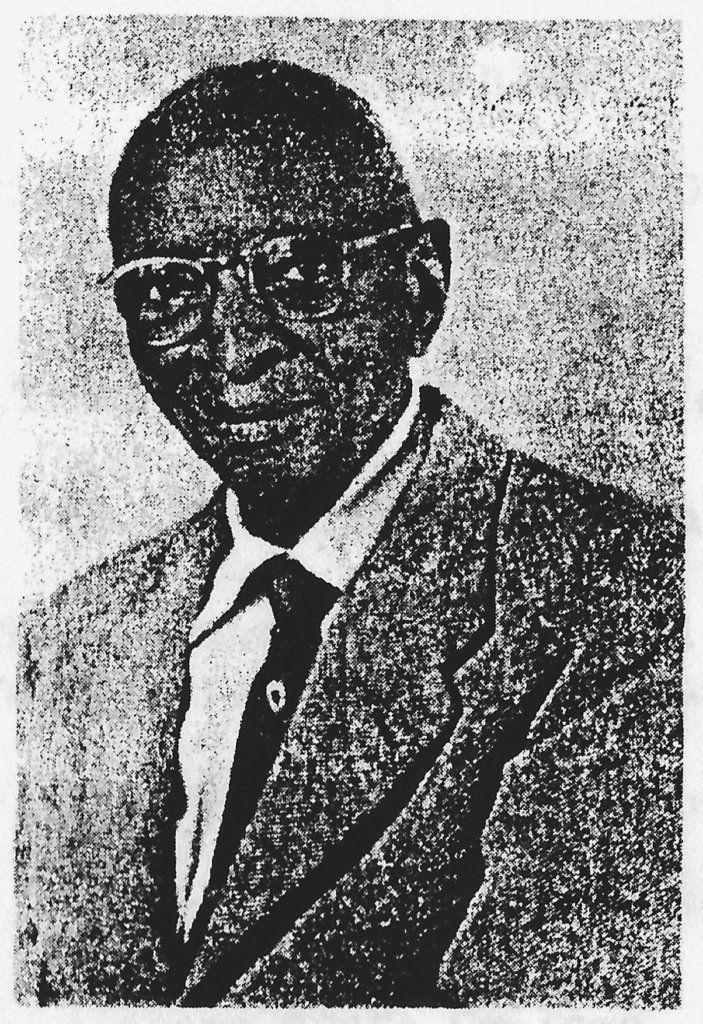

Dr. Roman T. Adair, one of the earliest Black physicians in Alabama.

Dr. Adair studied at the Alabama State Normal School for Colored Students in Montgomery (now historically Black college Alabama State University), a school that faced extreme opposition from white citizens for most of its early years. By the time of his death in 1961, he’d become one of the top surgeons in Montgomery, where he practiced for more than 50 years. He was renowned for dedication to his profession and for determination to provide the very best medical care to his community.

Dr. Adair lived and worked in an important place at an important time. He was a longtime member of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. led the congregation from 1954-1960, and where direct actions like the 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott took shape. In 1936, Dr. Adair founded the Negro Civic and Improvement League, which advocated for voting rights for African Americans against strong and often violent opposition. Later, this group helped lead early civil rights protests under another of its presidents, Rev. Solomon Seay of the historic AME Mt. Zion Church.

During these same years, Dr. Adair’s niece, Bessie Louise Adair, was growing up in Alabama. Soon, she and her parents would join one of the 20th century’s greatest demographic shifts and leave the South behind. Bessie would forge her own path more than 2,000 miles away from Alabama, eventually starting a family of her own and becoming mother to Billy Anfield and three daughters.

Northern migration

Bessie’s parents, along with thousands of African Americans looking for jobs during World War II, moved their family from the struggling South to the Northwest. They found work in the booming shipyards of Vanport, just north of Portland.

There, Bessie’s mother, Zelma, met William Anfield, a young Black man from Georgia who also worked in the shipyards. Like the Adairs, William had been drawn to Vanport by the promise of a better life with more opportunity. But unlike the Adair family, William was alone in Vanport. Zelma took pity on the young man and invited him to family dinner — where he met and he fell in love with her daughter, Bessie. She and William married in 1944.

In Vanport, the Adairs and Anfields had found a racially segregated community in a state that had long been unfriendly and unwelcoming to African Americans; until 1926, it was illegal for African Americans to live in Oregon. By the time Bessie and William arrived, at the end of World War II, Vanport officials were already planning to raze homes there to make way for industrial development —and to encourage its Black population to leave the state. When Vanport tragically flooded in 1948, the entire city of more than 15,000 people was wiped out in a single day. At least 15 residents were killed in the flood — although the pattern of racist behavior by housing and city officials makes many believe the number of deaths may actually be much higher. Bessie and William started looking for another place to call home and raise a family — which now included Billy, who was born just a few months later.

WWII veterans had GI Bill money to spend on new homes — but for Black veterans like William Anfield, money often wasn’t enough. William hoped to purchase a home for his young family in the east Portland neighborhood of Rocky Butte. His hopes were dashed by realtors and banks who had agreed not to sell to Black buyers in all but a few “undesirable” neighborhoods, in a racist practice now known as redlining.

Like many other Black families, the Anfields instead ended up in the Albina district, the only Portland neighborhood where Black men were allowed to purchase homes.

At home in the Albina district

Billy has fond memories of that house on North Haight Avenue.

“I remember sitting around our little kitchen table, listening to family stories. The kitchen was so small, whoever sat with their back to the oven had to move their chair so Mother could get to the biscuits,” he says.

Albina and the neighboring King district had become a thriving community. It was the center of life for Black Portlanders like the Anfields, many of them also displaced by the Vanport floods. At the same time, the neighborhood felt diverse to Billy. He remembers white folks, Japanese people who’d been held in internment camps during the war and Black families living side by side.

“Everybody worked so hard to make ends meet. We all shared what we had,” Billy recalls.

More recently, North Portland and its Albina and King districts have become increasingly gentrified, pushing Black Portlanders out. Read about how Central City Concern is helping to reverse this trend by providing affordable homes for displaced residents.

Working hard to build a good life

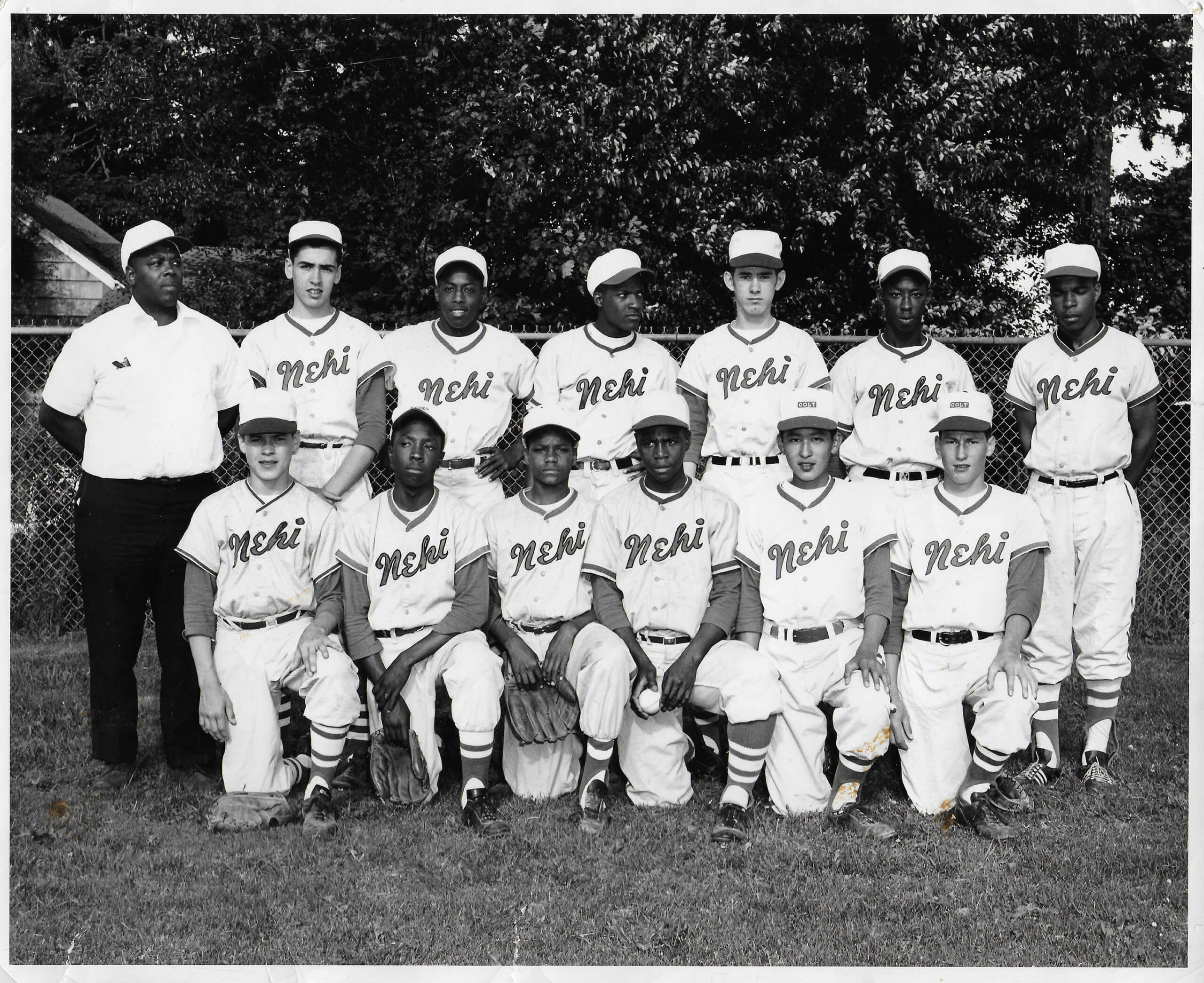

Billy’s father held two jobs, spending nights at the ESCO steel foundry and days parking cars downtown. His mother was one of the first Black woman to work for Multnomah County, first as an elevator operator in the county courthouse and then as a secretary for the environmental services department. Somehow, she also found time to serve as the first Black and first woman president of the Albina Little League during Billy’s baseball years.

Sometimes, while sitting around their little kitchen table with Billy and his three younger sisters, Billy’s parents shared stories about growing up in the Deep South.

“My mom would talk about the church bombings in Alabama. Dad would tell us about why he left Georgia – he said he would’ve been hung if he stayed. I’d think, ‘That’s not me. That’s not my life.’ I had my toys, my science set and art set,” he says.

To young Billy, North Haight Avenue felt full of hope. But there were clouds on the horizon.

The story goes on

Billy’s loving family imbued him with a sense of rootedness and responsibility for his community. He is part of a long tradition of service, from Dr. Adair in Alabama to his mother Bessie Louise in Portland and the Albina community.

As a young man, Billy lost his way. He spent 20 years in a fog of addiction before finding a path back to his family and the work he was born to do. Today, Billy’s eyes light up when he talks about his heritage, and how his family’s journey has echoed that of so many other African Americans.

Read Part 2 of Billy’s story to learn how he navigated through substance use disorder, started one of CCC’s first employment programs and built a three-decade career that has impacted hundreds of Portlanders.